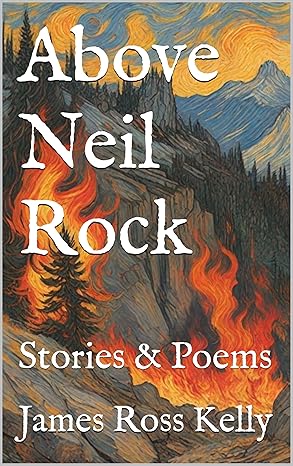

Stories and Poems by James Ross Kelly

Reviews

Publisher’s Weekly Booklife Reviews.

Kelly’s piercing collection of memoir pieces and poems leaves the reader with a vague ache in the heart. Jim, orphaned after his parents separate, is raised by his uncle and aunt in Southern Oregon, where his grandfather also comes to live with the family. In some ways it is an idyllic childhood, roaming the woods and working the farm, hunting and listening to his grandfather’s tales. But as he tries to live “an honorable life,” Jim also feels an undercurrent of loss as he yearns for his father, mother, and brother. As a veteran who is ultimately discharged with “no medals, no wounds, no horrific nightmare memories, but with a sense of the machine of military mind that operated on fear and redoubled itself with vast sums of money,” Jim contends and tries to come to terms with collective guilt, often doubting if humanity was humane enough.

While the material is often searching, many of the poems and pieces deal with the practicalities of logging. Kelly deftly juxtaposes the often violent lives of the people who make a living cutting down forests with the violence done to the trees, likening the work to nothing short of genocide. Kelly presents an empathetic insider’s account of hardworking, hard-drinking, generally short lives. Characters who linger include Jim’s grandfather who gets his son’s small farm up and running within a year of moving there; Richard Long, a six-foot-seven giant with “dinner-plate-size[d] hands”; and of course the towering conifers—anyone encountering one in the Cascades, he writes, would “approach this presence with awe.”

Lyric and moving, both prose and poems are shot through with an unnamable pain, a longing for something intangible. Kelly compares the evil in this world to a minotaur trapped in a maze, often breaking out and causing untold destruction. Kelly’s honest and unsparing gaze doesn’t absolve his own countrymen too, but he sees hope in the philosophy of universal love. A poignant read.

Takeaway: Profound, genre-crossing memoir of farm life, logging, and war and its costs.

Comparable Titles: Richard Powers, Howard White.

Production grades

Cover: A

Design and typography: A

Illustrations: N/A

Editing: A

Marketing copy: A-

Publisher’s Weekly–BookLife Prize – 2024

Plot/Idea: Above Neil Rock is an expert storyteller’s look back on a life full of ups, downs, and many seemingly-mundane moments that are brought to life through lyrical prose and poetry. The reader may be reminded of Bret Harte’s work, if Harte had lived in “the bloodiest century of human existence” and experimented with LSD.

Prose: The memoir’s writing is exceptionally beautiful, even–or, perhaps, especially–when discussing some of the hardships in the author/narrator’s life. Scenes from his childhood that depict the expansive Kansas prairie and later scenes set in nature shine as well. They depict a bygone time, not necessarily with nostalgia, but with poignant candor.

Originality: Telling a memoir through vignettes and poems that don’t always share direct linear plot threads is a risky narrative move, but it’s one that James Ross Kelly pulls off remarkably well. Above Neal Rock is an engrossing read, both because of the author’s varied life experiences and because of the unique, lyrical voice with which these experiences are recorded. The reader may note some outdated language that may cause readers to bristle. It is also true that the worlds depicted are overwhelmingly masculine spaces. However, there is a level of honesty and self-awareness to the narrator that will endear him to readers.

Character/Execution: Each vignette creates a new stitch of Americana–whether the dusty fields of 1950s Kansas or Haight-Ashbury, San Francisco in 1970–that brings these times and places alive. “La vie en rose” is a timely, heartbreaking piece that brings the memoir into our own precarious time in history. It will resonate with many readers.

Blurb: James Ross Kelly’s masterful storytelling and departure from a traditional memoir model makes the author’s experiences come alive for readers.

Reader’s Favorite

5 Stars–Reviewed by K.C. Finn for Readers’ Favorite

Above Neil Rock: Stories & Poems by James Ross Kelly is a memoir that captures the rugged beauty and harsh realities of life in the Pacific Northwest. Through a blend of stories and poems, Kelly reflects on the environmental devastation caused by corporate silviculture, the extinction of indigenous cultures, and the personal struggles of his upbringing. His writing, deeply rooted in experience, conveys a love for the land and a mournful awareness of its losses. Kelly’s work is both an homage to nature and a critique of the forces that have shaped, and often harmed, the region. Kelly offers a narrative style with an authentic, lived-in quality that brings the Pacific Northwest to life with precise detail, and the striking sense that every moment he chooses to document carries huge emotional weight behind it.

James Ross Kelly’s ability to blend this narrative with broader environmental and cultural issues is immense, and it’s clear that a lot of interconnected thought has gone into the construction of this work to offer a poignant snapshot of the dangers of money-minded silviculture. Kelly’s courage in confronting painful memories and societal injustices lends a raw honesty to this work, and his poetic use of language is powerfully impactful, with memorable phrases that resonate long after reading. I was particularly struck by the imagery of ‘The Forester’ in which the call of the elk and the screaming cables of the logging industry create a horrendous, ill-fitting harmony in the decimated woodland. Overall, Above Neil Rock is a deeply impactful and relatable memoir that I highly recommend to those interested in personal stories, but also those keen to preserve the lands they’ve grown up in and celebrate them.

Reviewed by Doreen Chombu for Readers’ Favorite

5 Stars–Reviewed by Doreen Chombu for Readers’ FavoriteAbove Neil Rock is a collection of stories, poems, and prose by James Ross Kelly. It combines personal and familial stories set against great social commentary. The book covers stories from the author’s childhood, including the warmth of Christmas, learning farming from his grandfather, and fishing and swimming with friends. It also delves into the complexity of family life, such as his father’s PTSD from fighting in WWII, his mother’s struggle with sobriety, and the grief of losing his brother. The author gives an account of his military experiences, detailing the joyful times as a group and the gloomy memories of losing friends. He narrates hilarious stories that shaped his understanding of the world and his experience of planting trees and dealing with loggers. From relationships and fatherhood to guilt and social views, Kelly discloses his most vulnerable moments and deepest thoughts. Above Neil Rock is a captivating book that will take you on a roller coaster of emotions. James Ross Kelly jumps from one event of his life to the next with detailed descriptions that will make you laugh or cry. His reflections are thought-provoking, delving into the beauty of nature, the importance of hard work, morality, responsibility, and the impact of genocides and political unrest. The author is an engaging storyteller and poet, drawing readers into his narrative with a unique blend of humor and drama. The poems complement the narration as they are perfectly placed in the story, enhancing the emotional depth of each chapter. The author tackles issues like environmental protection, the current political climate in the United States, the Holocaust, the foster care system, addiction, and abortion, treating each with the utmost sensitivity and respect. The stories about his family and community perfectly illustrate the interconnectedness of human experiences and highlight the weight of personal and collective history. Overall, I enjoyed reading Above Neil Rock and learned many lessons from the author’s experiences. This book is a great read, and I recommend it to anyone who loves memoirs with poetry and social commentary.

Reviewed by Rabia Tanveer for Readers’ Favorite

5 Stars–Above Neil Rock: Stories & Poems by James Ross Kelly is a memoir in which the author recounts his life and shares the past with poems and short stories. The author takes the reader through his life from 1952 when he worked different jobs. From farming, ranching, and then joining the US Army, the reader experiences everything with him through his prose and poems. Stories like “Why the Fairy Shrimp Left” gave a realistic yet very personal look into the life of the author. “The Red Gate” showed an emotional look at his time on the farm. It was filled with nostalgia and a bittersweet type of pain that I could also feel. Above Neil Rock by James Ross Kelly gives the reader a glimpse into his heart and mind. However, these stories and poems also offer a glimpse into the lives of those who call the Pacific Northwest home and give us a look at working-class families who have struggled to survive during tumultuous times. The author’s writing is infused with a sense of urgency and a deep love for the natural world. While he recounts his past, Kelly isn’t bitter or angry; he is nostalgic and even sad in certain parts. I found comfort in his narrative style; it felt like he was a long-lost friend whom I met again after a long time. I enjoyed the pace that seemed to follow the ups and downs of Kelly’s life. The attention to detail, the way he described his emotions and the way he didn’t shy away from baring his soul had me hooked until the end. I know I will be revisiting Above Neil Rock very soon!

by James Ross Kelly

by James Ross Kelly